Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera /Department of Government, The University of Texas at Brownsville / Critical Reviews on Latin American Research / diario19.com

A new model of organized crime has emerged in Mexico, Central America, and other parts of the Americas. The pioneers of this model are the Zetas, an organized crime group that originated in the northeastern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, which borders the U.S. state of Texas and the Gulf of Mexico. The Zetas have introduced a military culture and highly sophisticated weaponry to the enforcement methods of criminal organizations. These ultra-violent and brutal methods, coupled with complex business-like strategies and a rupture with past governmental relations in a new democratic era, have permitted the evolution of drug traffickers into transnational entities. These new crime syndicates have critically altered the political, social, and cultural dynamics of Mexico and neighboring countries in Central America. The dominance of the Zetas has given transnational criminal organizations unparalleled economic power, and, in the process, violence against individuals and communities has increased to unprecedented levels.

In his most recent book, La Guerra de Los Zetas: Viaje por la Frontera de la Necropolítica, journalist Diego Enrique Osorno relates stories about the Zetas’ deadly encounters in northeastern Mexico. Osorno, in the role of a war correspondent, uses what is known as narrative journalism or literary journalism to explain violence in this region and to give a voice to the terrified people living there. From 2010-2012, he travelled through troubled towns and cities in the states of Nuevo León and Tamaulipas chronicling the avalanche of increasingly heinous crimes after former Mexican President Felipe Calderón declared a “war on drugs” in 2006. La Guerra de Los Zetas is one of dozens of trade books reporting events and individual experiences of Mexico’s narco-war, but it is not part of the scientific debate on organized crime

The concept of death is one of the central elements in Osorno’s narrative of his sad journey through the two Mexican states. Aside from the word “death” (muerte), Osorno uses multiple expressions for it, such as “place of death” (lugar de muertos), and the word “to kill” (matar). La Guerra de los Zetas is drenched in death and bloody killings. It includes stories related to the assassination of a mayor in Santiago, Nuevo León; the veneration of death through the cult of the “Holy Death” (Santa Muerte); what the author considers as a “positive” story about the career of a mayor who knows “how to kill”—to defend the residents of the rich Mexican municipality of San Pedro Garza García in Nuevo León; and an account of death and destruction in a Mexican border town (Ciudad Mier, Tamaulipas).

In his concluding chapter, Osorno attempts to explain violence in Mexico by employing Achille Mbembe’s theoretical framework of “necropolitics:” the politics of death. Necropolitics, according to Mbembe, is a contemporary form of subjugation of life to the power of death. However, lacking in Osorno’s narrative is a thorough understanding of the concept of “necropolitics,” which also appears in his subtitle. Similarly, it is not clear that he fully appreciates the complexity of French scholar Michel Foucault’s thinking about power. It is crucial to the concept of necropolitics in analyzing violent reality in some weak, failing African states—but not in a robust country such as Mexico.

Engaging prose on this topic should include not only stories, but thoughtful analysis or new information that serves as a springboard for further exploration. La Guerra de los Zetas falls short. The author’s ideas are not well articulated and the main account lacks appropriate context, because of its limited coverage of the relevant stories. The author also makes several major assertions without citing his sources or providing adequate evidence for them. For example, Osorno suggests that former President Calderón declared a war on drugs with the sole aim of legitimizing his arrival to power after the contested election of 2006 (31). Reality is much more complex, as a war correspondent would know from experience. As a chronicler (cronista) or literary journalist he should provide a descriptive, accurate context that helps the reader understand complex phenomena.

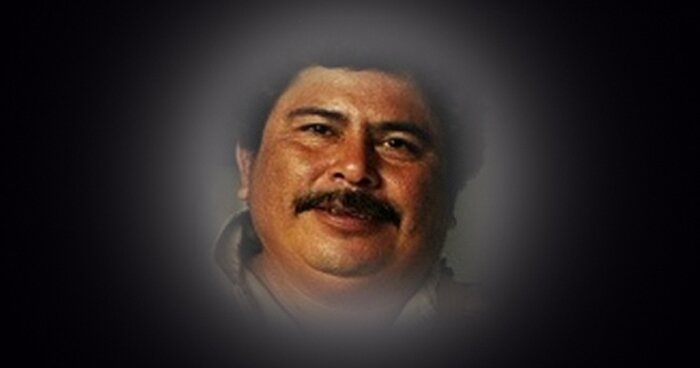

The most revealing part of Osorno’s book are the stories written by Oscar López Olivares (El Profe), an alleged co-founder of the Gulf Cartel, the organization that eventually gave birth to the Zetas. Osorno reproduces parts of El Profe’s memoirs that provide a first-hand account of the origins of the Gulf Cartel and its operations. When comparing Osorno’s stories with the account of El Profe Olivares, the difference in terms of information and quality is evident, revealing El Profe’s extensive understanding of politics and organized crime in Mexico. Osorno drops the names of famous writers, such as Juan Villoro (who wrote the preface), Jon Lee Anderson and Alma Guillermo Prieto. But the name dropping cannot substitute for a thorough understanding of the subject matter.

La Guerra de Los Zetas fails to live up to its title, which suggests that the reader will gain new knowledge about the inner workings of the Zetas. In Osorno’s text it is difficult to identify the main national and international political actors and interest groups. Neither can the reader clearly identify who really benefits from the extreme violence. Osorno’s account is limited. It is centered on two Mexican states and does not acknowledge or mention the strong presence and connections of this group in other parts of the world. The Zetas also have an important presence in Central America where their practices and violence have impacted social dynamics throughout the region.

This is just one of many recent works in the same vein sensationalizing violence and mystifying some key events and actors involved. Basic questions still remain unanswered. Who really are the Zetas? How have they grown to become a power dominating large parts of Mexico, as well as nearby Central American countries, diversifying their activities both nationally and internationally? Who has contributed to the Zetas’ expansion? What are their links to Mexican politicians and foreign actors? Who has benefited from the Zetas’ model? It seems inconceivable—as Osorno’s account suggests—that the Zetas are just a hyper-violent group of killers (sicarios) using barbaric tactics to commit extortion, kidnap for ransom, and compete in the drug market with other Mexican drug cartels.

Diego Osorno’s book is not without virtue. It gives voice to victims of this very complicated problem by telling their poignant stores. Credit should also be given to the excellent marketing by Grijalbo and Random House Mondadori, the publishers, for successfully selling a text that is not different from the dozens of commercial books on Mexico’s narco-war. Nowadays, selling “blood” has become a profitable business in Mexico. However, publishers in the United States and Mexico should focus on promoting books that strive to answer the key questions of a drama that has spilled across national borders.

Este artículo fue originalmente publicado en Critical Reviews on Latin American Research 2014 http://www.crolar.org/index.php/crolar/article/view/107/html_52